China has for decades been among the world’s leading manufacturers and exporters, due mainly to its low labor and land costs. However, over the last few years, the rate at which China labor costs have been growing, and the ever-increasing cost of land, has left many people to wonder if the reign of China as the world’s most cost-effective workshop might be coming to an end.

China has for decades been among the world’s leading manufacturers and exporters, due mainly to its low labor and land costs. However, over the last few years, the rate at which China labor costs have been growing, and the ever-increasing cost of land, has left many people to wonder if the reign of China as the world’s most cost-effective workshop might be coming to an end.

Rental and purchase prices for factory land in China have been going up for over a decade. Average factory salaries went up over 30% in 2011, and the increase in 2012 is expected to exceed 11%. In Guangdong, for example, minimum wage is set to increase by at least 15% through 2015. Industrial land costs in China also have been on the rise. The natural result of this is that suppliers (and customers) are looking for cheaper markets to outsource their lower-value manufacturing.

Can China continue to survive as the world’s workplace?

Alternative Locations of Production

Alternative Locations of Production

There are several alternatives that have frequently been short listed as attractive alternatives to China as a location of production. However, while each country does have some persuasive arguments that would encourage manufacturers to consider them as a viable alternative, there are still some overriding deterrents.

Vietnam is cheap, but its pool of resources does not run nearly as deep as China’s. New labor laws and increased labor costs are being discussed; strikes are all the more frequent. As a result, Vietnamese factories are becoming increasingly difficult, and expensive, to staff. Logistics in Vietnam are poor compared to China and hence Vietnam might not be the best answer for China Coastal factories trying to run away from increasing costs.

Myanmar has the potential to become one of the next big manufacturing hubs, but US sanctions will not be dropped overnight. With only 60 million people, the population of Myanmar has about half the population of Henan, an average-sized Chinese Province. Logistics and an under-developed supply chain also make Myanmar a far less than attractive option for most factory owners at this time.

Cambodia is still a ways away from developing the logistics and skilled workforce required to become an immediate replacement option for China manufacturing.

India has always been plagued by low worker productivity, poor infrastructure, and has suffered from a lack of a clear and united Government vision to help it take the next step. Labor issues are abundant these days in India, and roads and ports are in poor conditions compared to those in China.

In general, labor and land costs in many of these countries are rising as fast, or faster, than in China.

So looking at the next 10 years or so, who will be the next China? Some suppliers have indeed run off to Cambodia, or Bangladesh, but more and more Chinese suppliers are looking much closer to home.

The next China might actually be Inland China.

In reviewing China’s 12th 5-Year Plan (December, 2010), it becomes clear that one of the Government’s main goals is to balance the economy and to spread economic wealth to a greater proportion of Chinese citizens. It is becoming more and more apparent that the China Government does not want to provide any more jobs for migrant workers in the Pearl River Delta region, but instead wants these migrant workers to return home and provide their labor to the Central, inland Provinces.

High land and labor costs have been the story throughout China over the last few years. Land prices all over China have until recently been on the rise, but land costs are still substantially lower Inland, than on the Coast. Salary figures show the same. Inland China has had its share of increases, in some cases rising faster on a percentage basis than the costs on the coasts, but the average salary still remains substantially lower as you move inland.

The minimum salary, in 2011, in Guangzhou, for example, was RMB1300 per month. In Shanghai, that number was around RMB1120, Hangzhou, RMB960, and Ningbo, RMB1200. Inland, however, the highest minimum wage would be Wuhan, at RMB900/month, and from there it drops even further. Minimum wages in Chengdu (Sichuan) are around RMB850/month, in Zhengzhou (Henan) they are RMB800/month, Hefei (Anhui) they are RMB720/month, and Nanchang (Jiangxi) about RMB720/month. The numbers seem to indicate that, as far as labor costs go, Inland China looks to be as competitive as the Coastal Cities were at the height of the China manufacturing boom.

Inland China’s Strategic Advantage

Inland China’s Strategic Advantage

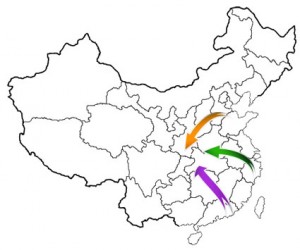

Allowing some minimum wage discrepancies to exist is a key signal that China is trying to lead the manufacturers inland. Of equal impact and importance, however, is that China has been intentionally providing competitive advantages for the poorer Inland Provinces, and this has led many manufacturers to shift their production to these less-developed regions. Massive China government investments in airports, high-speed railways, and highways in the inland provinces of China (Henan, Anhui, Hubei, Jiangxi, Shanxi, Sichuan etc.), are examples of this type of stimulus.

On top of transportation improvements and preferential minimum wages, the last few years have seen the Chinese Government provide Inland China with tax benefits, rent subsidies, and other preferential policies, all set up to lure investors to inland China. Seeing their own costs soar, Coastal factories are reacting to this stimulus. This is changing the manufacturing landscape in China.

The Chinese Government has stated they will plan a 4th ‘Economic Hub’ in Central China, including Hubei, Hunan and Jiangxi provinces. The plan is for these three provinces to outgrow the rest of China substantially in the next 10 years. Li Hongzhong, Hubei’s Party chief, has said that the province’s gross domestic product could double to 3 trillion Yuan by 2016, from 1.5 trillion Yuan last year, as more factories are relocated to the province. We can expect to see similar growth numbers in other Chinese Provinces over the next few years, even as China’s share of world manufacturing drops.

Big-name firms have already started taking advantage of incentives to move to the Inland of China including Foxconn ( Henan) Unilver (Anhui) Midea (Anhui) , Konka (Anhui) , Chrysler (Sichuan), Hewlett-Packard (Sichuan) , Intel (Sichuan), Quanta (Sichuan) L’Oreal (Hubei) and others that previously had their factories based in Coastal Cities in China.

A knock on consequence is that lower value-added, sub-suppliers of these larger manufacturers are also moving inland, taking advantage of savings, while at the same time wanting to be close to their customers. This factory migration is not only a case of large multi-nationals moving inland, the average smaller supplier is also investigating, and reacting to, the impacts of moving inland.

Inland China’s Cost Disadvantage

Inland China’s Cost Disadvantage

Of course, certain increased costs for suppliers cannot be avoided when a move is made inland. Their supply chain becomes more geographically spread out. Inland shipping costs increase. Factory owners have to deal with a different culture of workers, and different culture of local Government, language barriers, higher levels of corruption, etc. All of these factors do indeed provide sometimes costly barriers to entry.

These barriers, along with incentives from abroad, inevitably lead to there being industries that start to shift production away from China (Bangladesh, for example, has taken much low-end textile work from China, and now owns a 6% share in the global garment and textile industry). This has been happening and will continue to happen. But data coming out of China’s inland provinces seem to indicate that despite these barriers, the largest representation of manufacturers that are arriving in Inland China have been from the Coastal Cities of the Pearl River Delta.

In Henan, for example, the number of workers migrating to other provinces was roughly 17 million in 2006. In 2011, that number was closer to 12 million. Similar numbers are being found in other inland provinces. Workers are going (or staying) where they can find work. Increasingly, this work is being found in Inland China.

Over the last century we have witnessed low-cost, labor-intensive industry move from Japan, to Hong Kong, to Taiwan, and then to China. In each case, a Country will gradually build up skills and capital, leaving the lowest rung of manufacturing to the poorer country. This currently seems to be happening in China, but now the relocation is happening within a single country. Many suppliers will relocate to other countries – this is inevitable. But it does not look like the next 10 years or so will see China lose as large a share of their world exports to its Asian neighbors as many people are expecting.

The reasons to suspect that China is still the best place to be for the majority of Chinese manufacturers are numerous. Efficient supply chains, a fully-developed infrastructure, relatively low wages, a consistent and stable government, and an increasingly productive and skilled workforce, are among these reasons. Also, for many manufacturers, China is where their sales are growing fastest. Add to this the fact that the Chinese Government (and its’ fat wallet) is ‘pushing’ suppliers towards Inland China, through various incentives, bodes well for the future of Inland China’s manufacturing base.

Manufacturers will have to work through this transition. It will not be easy. However, the transition from Coastal China to Inland China would intuitively seem to be a much more fluid and seamless transition than would that to an entirely different country.

China, to be sure, is looking forward to the day when all the low-value added manufacturing is conducted outside of its borders. They have seen the quality of life go up for Chinese citizens, in all Coastal Cities, as a result of being the ‘World’s Workshop.’ The next phase for China is to see Inland China go through the same transitions that we saw on the Coast. The first part of that phase is an influx of low value-added manufacturing. Perhaps in another 10 years or so, we will see Inland China become as prosperous as Coastal China. At that time, China will be more than happy to see this manufacturing go elsewhere. Until then, it looks like Inland China is going to be one of the top choices for suppliers looking for alternatives to the expensive Coast.